When I first moved back to my little town of Clinton, Arkansas, more than two years ago, it was primarily to finish working on my book, which is a memoir about growing up in my small town, my childhood best friend, and what happened to each of us when our lives diverged after high school. Through that very personal, small story, I hope to illuminate some broader trends: the divide in life expectancy among the least educated Americans, geographic inequality, and how this country treats girls and women.

It’s one of the first times I’ve embarked on something so deeply personal. I became a journalist almost sixteen years ago, when I enrolled in the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. I didn’t know very much about journalism when I applied. What I did know was that all of the authors I had admired growing up had begun their writing lives at newspapers. I also knew that the work I was doing for an agency in New York City that investigated complaints of police misconduct was not satisfying. I interviewed New Yorkers on a daily basis about what was often the worst moment in their lives, but I had little power to help them or affect the forces arrayed against them. Worse, I had to keep their stories private and, at the same time, render judgment on them. I knew both that more people needed to know about those stories, and that doing that kind of work was not the way to tell them.

It’s fair to say this history influenced my journalistic philosophy. Small stories about individual people are the best way to illuminate bigger stories about the way we live. I began doing that in earnest as a senior writer at The American Prospect, where I started to publish articles about how working-class families had suffered during The Great Recession and were recovering it (or not.) I wrote about a woman in Kentucky and her family; I wrote about Elizabeth Warren, The Great Recession’s Cassandra; I wrote about families living in a hotel after they lost their housing; I wrote about how the housing crash had wiped out almost a generation of black wealth in one of the country’s wealthiest black enclaves; and I wrote about how inequality was killing a very specific group of women. I’ve also written about people living in their cars in Silicon Valley; about rethinking a small town in coal country; and about the painful death of my hometown’s library. The subject of my book is along similar lines, about how inequality is killing people, including those I love, with whom I grew up in Clinton. In some ways, all of my work has been leading back here. I traveled to places that reminded me more and more of home, and met people that reminded me of my own family, until finally I decided to write about myself.

Coming home has been educational in almost every way. I have been critical of my hometown in recent posts, but I should say very clearly that I also love it. Why would I bother to criticize it otherwise? Since I’ve been back, I’ve found myself driving down the old road, Shake Rag Road, where my mom’s parents once lived. Some of my family still lives at the end of it, on more than 100 acres that has been in the family for the better part of a century. We’ve always called it, somewhat ambitiously, The Farm. The Farm never produced much, and the people who lived on it have always had to work other jobs to make a living.

For various reasons that can be summed up with the word “family,” my grandmother’s house on The Farm is empty now. The wood siding has buckled and her rose bushes are wild and overgrown. The driveway toward The Farm is too ragged and rocky for my car, but I still drive down Shake Rag Road often and look at the land as I pass, just checking in. When I was growing up, we used to joke that my grandmother literally lived over the river and through the woods, and Shake Rag does indeed travel over a river, on a one-lane bridge, and through a woods. I have always remembered the big live oak about halfway down, spreading out like a parachute in the middle of a field full of cows, and clocking its change through the seasons like a friend that is seen too infrequently but always fondly. What I didn’t remember about that drive until I made it more recently was how perfectly the mountains behind the field frame that tree and that field, forming a wall colored now with a vibrant multi-hued green of new Spring leaves, some so bright they are almost neon. I also didn’t remember that, right before I get to The Farm the road dips down toward a river valley so that the canopy of oak and pine envelopes me, closing in, obscuring the mountains and everything else except the land and the woods in front of me. I don’t know what my family should do with this land, but I do know that it’s ours. You don’t get to choose what you inherit, and I feel my future bound to it, responsible for it, in some way.

I am still working out what exactly that means, but I haven’t been able to turn off being a reporter here. I’ve started casually looking at our institutions and infrastructure with the concerned eye of a citizen who relies on them; once I start asking questions, everything seems to collapse under the weight of scrutiny. To take one recent example, I’ve been hearing a lot of grumbling about the local hospital, which is run by a nonprofit called Ozark Health, Inc. I had been concerned anyway because the hospital administration was relatively quiet in the early weeks of the Covid-19 pandemic. It didn’t make any announcements, offer any community guidance, or make its plans public, which is odd, because it’s one of the biggest institutions in the county, and the only hospital for miles. Worse, the director of nursing had taken a vacation to Florida in the third week of March, just as everyone else was canceling plans. Because I’m a reporter (with nothing to lose) several people reached out to me about two early cases of the disease associated with the hospital, about which the hospital’s administration had remained silent. They did not answer questions or offer full information. Secrecy never works—the truth always comes out—and this is doubly so in a small town where everyone knows everyone else. I wrote about some of these issues in several posts on Facebook, frustrated because I didn’t have an easy local outlet at which to publish but also worried that the public needed to know how these issues were being handled (or weren’t.) In the process of looking into the hospital, I requested its latest 990s, the tax forms nonprofits must file every year. Federal law requires that nonprofits make these available for public inspection during work hours. It is routine to request them of nonprofits, and it should be routine to provide them to the public. I called twice asking to be able to see them and possibly receive copies, for which I offered to pay. I asked to speak to an official who could provide me with answers, and both times was routed to an answering machine. I left messages, and gave the hospital a week to respond each time. They never did. I’ve requested 990s from other nonprofits here in the past, and they’ve often either not provided them, ignored me, or joked that they hadn’t gotten around to doing it yet. These are serious lapses, and they’re just as critical in a small town and as they would be anywhere else. I’ve always gotten quick responses to requests for data from city and county officials, but the truth is, many don’t have the capabilities to collect the data I’m asking for. This lack of information on the one hand, or not taking seriously the duty to provide information on the other, troubles me. What else are big institutions like the hospital ignoring? How do they treat normal citizens less familiar with the law, less pushy and sure-footed, when they ask for information?

There are people who press these issues, and a lot of people who work hard to bring positive change here, but it’s often individuals working against an overwhelming sense of stasis. But there’s another problem. I don’t know if it’s a Southern quality, or a small-town quality, or a human quality that is amplified when a small number of people need to get along and lose the anonymity that facilitates disagreement, but people here, mostly, avoid conflict. There just aren’t very many fights and arguments and big debates. Maybe it’s because there aren’t very many outlets for it, because there isn’t a big town hall with meetings and microphones to amplify voices. Or maybe it’s because people know the likelihood of seeing their rivals the next day is very high. There’s another attitude I encounter a lot, too, which is that people aren’t used to disagreeing without any ill will. But argument is important. It’s how and why important changes happen. Argument enables people to push back against bad decisions. Argument holds people accountable.

I haven’t decided yet, exactly, how I balance my sense of obligation to this place with what I think it needs, and how to use my skills as a journalist to shake things up. What I do know is that I think it’s important, and that small towns can tell big stories. Which is why I’m here, and why I’m glad you’re here.

As I think about the shape that Welcome Home takes, I would love to hear from you all about the kinds of stories you’d like to read, and the work you’re interested in supporting. I will open up a discussion thread associated with this post, and will monitor it and answer any questions you all have through the next week.

What I’m Reading and Listening To:

I haven’t been able to stop listening to the Fiona Apple album; I am mourning New York City; and we are living in a failed state.

What I’m Looking At:

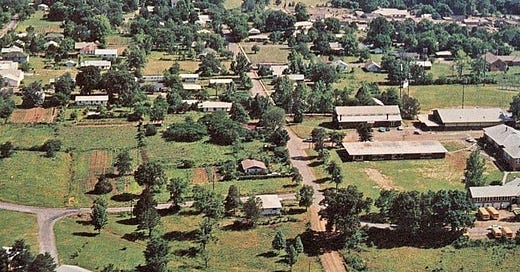

I can’t get over these pictures of my hometown’s downtown in 1969. The dirt road that runs through the center of the photo is a major street, along which the high school sits. This is also, today, one of the most densely packed neighborhoods in the entire town of Clinton, but just a generation ago it was full of garden plots. There is now a five-lane highway running along the town, on the far right of this picture, but back then it was just trees and fields and a river valley. It’s such a familiar landscape in such an unfamiliar situation that my mind refuses to become oriented to it. I just keep staring.

Cute Animal Pic of the Week:

Hunting dogs here are often discarded. Some hunters love their dogs and treat them like family. Others, sadly, treat them like equipment that either serves them well or doesn’t. If a hunting dog gets too old, or lost in the woods, or can no longer hunt because of an accident, it’s often left behind to die. Every fall and winter, these “lost” dogs show up and fill local shelters or stumble into people’s yards looking for food. Those are the lucky ones. It is amazing how resilient they are, and how quickly they rebound to trust people again. I don’t know Annie’s exact story, but I know she’s a big hound with floppy ears. What more could you ask for in a dog?

I really enjoyed this Monica. Thank you for sharing!

great insight and commentary :) thank you!